The electoral victory of center left regimes in at least three Latin American countries, and the search for a new ideological identity to justify their rule, led ideologues and the incumbent presidents to embrace the notion that they represent a new 21st century version of socialism (21cs). Petras undertakes a verification and comparative-historical analysis of this tenet by putting Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador under the loop.

Introduction

Prominent writers, academics and regime spokespeople

celebrated a totally new variant of socialism, as completely at odds with what they

dubbed as the failed 20th century, Soviet-style socialism. The advocates and publicists of

21cs claims of a novel political-economic model rested on what they ascribed as a radical

break with both the free market neo-liberal regimes which preceded, and the past “statist”

version of socialism embodied by the former Soviet Union as well as China and Cuba.

In this paper we will proceed by examining the variety of critiques put forth by

21cs of both neo-liberalism and 20 century socialism (20cs), the authenticity of their

claims of a novelty and originality, and a critical analysis of their actual performance.

The 21cs Critique of Neo-Liberalism

The rise of 21cs regimes grew out of the crises and demise of neo-liberal regimes

which pervaded Latin America from the mid 1970’s to the end of the 1990’s. Their

demise was hastened by a string of popular uprisings which propelled the ascent of

center-left regimes based on their rejection of neo-liberal socio-economic doctrines and

promise of basic changes favoring the great majorities. While there are important

programmatic differences among the 21cs regimes, they all shared a common critique of

six features of neo-liberal policies.

(1) They rejected the idea that the market should have precedence and dominance

over the state, by which they meant that the logic of capitalist class profit

maximization should exclusively shape public policy. The collapse of the

market driven capitalism in the recession of 2000 -2002 and mass

impoverishment discredited the doctrine of “rational markets” as banks and

business bankruptcies skyrocketed, the middle class lost their savings and the

streets and plazas filled with unemployed workers and peasants.

(2) The 21cs regimes condemned deregulation of the economy which led to the

rise of speculators over an above productive capitalism. Under the aegis of

neo-liberal rulers regulatory legislation in place since the Great Depression

was abrogated and in its place, the policies of capital controls, and financial

oversight were suspended in favor of a “self-regulated” regime in which

market players established their own rules, thus leading, according to their

critics, to speculation, financial swindles and the pillage of public and private

treasuries.

(3) The predominance of finance over production was the centerpiece of the anticapitalist

discourse of the 21cs regimes. Implicit was a differentiation

between ‘bad’ capitalism which earned wealth without producing goods and

services over ‘good’ capitalism, which presumably did produce value of social

utility.

(4) Related to its overall critique of neo-liberalism was a specific critique of the

lowering of tariff barriers, the privatization of public enterprises at below their

true market value, the denationalization of ownership of strategic resources

and the massive growth of inequality.

(5) The 21cs argued that neo-liberal regimes surrendered the economic levers of

the economy to private and foreign bankers (like the IMF) who imposed

deflationary measures instead of reflating the economy through infusions of

stale spending. The political leaders of the center-left used this critique of

neo-liberalism and the implicit future promise to break decisively with neoliberal

capitalism, without committing themselves to a specific break with

capitalism of another variety.

While the center-left critique of neo-liberal capitalism appealed to the popular classes,

their rejection of 20cs, was directed at the middle class and to reassure the productive

classes (business class) that they would not encroach on private ownership as a whole.

Critique of 20th Century Socialism

In a kind of political balancing act to their opposition to neo-liberalism, 21cs

advocates have also put distance to what they dub “twentieth century socialism”. Partly

as a political tactic to disarm or neutralize the numerous and powerful critics of past

socialist regimes and partly to further claims of a novel, up-to-date variant socialism in

tune with the times, the 21cs make the following critique and highlight their differences with 20th century socialism.

(1) Past socialism was dominated, by a heavy handed bureaucracy that

misallocated resources and stifled innovation and personal choices.

(2) The old socialism was profoundly undemocratic both in the way it ruled, the

organization of elections and the one part state. The repression of civil rights,

and all market activity figures large in the 21cs narrative.

(3) The 21cs conflate democracy as a system with the electoral road to power or

regime change. Changes of government resulting from armed struggle,

especially guerilla movements are condemned, though all three 21cs

governments came to power via elections which followed popular upheavals.

(4) One of the key arguments put forth by 21cs regimes is that in the past

socialists failed to take account of the specifications of each country.

Concretely they emphasize differences in racial, ethnic, geographic, cultural, historical traditions, political practices etc. which are now considered in defining 21st cs.

(5) Related to the previous point 21cs emphasize the new global configuration of

power in the 21st century which shapes the policies and potentialities of 21cs.

Among the new factors, they cite the disappearance of the former USSR and

China’s conversion to capitalism; the rise and relative decline of a US

centered global economy; the rise of Asia, especially China; the emergence of

Venezuelan promoted regional initiatives; the rise of ‘center-left’ regimes

throughout Latin America; and diversified markets, in Asia, within Latin

America the Middle East and elsewhere.

(6) The 21cs regimes claim that the “new configuration of society and state” is

not a ‘copy’ of any other past or present socialist state. It is almost as if every

measure, policy, or institution is the design of the contemporary 21cs regime.

Originality or novelty is an argument to enhance the legitimacy of the regime

before external and internal critics from the anti-communist Right and to

dismiss substantive criticism from the Left.

(7) The 21cs regimes make a point of emphasizing the fact that the leadership has

no links past or present with Communism and in the case of Bolivia and

Ecuador openly reject Marxism both as a tool of analysis or as a bases for

policy prescription. The exception is President Chavez whose ideology is a

blend of Marxism and nationalism linked to the thought of Simon Bolivar.

Both Correa and Morales eschew class divisions, counterpoising a ‘citizen’s

revolution’ against a corrupt party oligarchy, in the case of the former, and a culturally oppressed Andean Indian communities against an “European

oligarchy”.

Critique of 21st Century Socialist Regimes

While 21cs regimes have more or less clearly stated what they are not and what

they reject in the past both on the Left and the Right, and have in general terms stated

what they are, their practices, policies and institutional configurations have raised serious

doubts about their revolutionary claims, their originality and their capacity to meet the

expectations of their popular electorate.

While a number of ideologues, political leaders, and commentators refer to

themselves as 21cs, there is a great variety of differences in theory and practice between

them. A critical examination of the country experiences will highlight both the

differences between the regimes and the validity of their claims of originality.

Venezuela: The Birthplace of 21cs

President Chavez was the first and foremost advocate and practioner of 21cs.

Though the following presidents and publicists in Latin America, North America and

Europe have jumped on the bandwagon; there is no uniform practice to match the public

rhetoric.

In many ways President Chavez’s discourse and the Venezuelan government’s

policies define the radical outer limits of 21cs both in terms of its foreign policy

challenging Washington’s war policies and in terms of domestic socio-economic reforms.

Nevertheless, while there are innovative and novel features to the Venezuelan model of

21cs, there are strong resemblances to previous radical populist – nationalist regimes in

Latin America and European welfare state reforms.

The most striking novelty and original feature of Venezuelan versions of 21cs is

the strong blend of “historical” Bolivarian nationalism, 20th century Marxism and Latin

American populism. President Chavez conception of 21cs is informed and legitimated by

his close reading of the writings, speeches and actions of Simon Bolivar, the 19th century

founding father of Venezuela independence. Chavez’s conception of a deep rupture with

imperial powers, the reliance on mass support against untrustworthy domestic elites

capable of selling out the country to defend their privileges is deeply embedded in his

readings of the rise and fall of Simon Bolivar. Though Chavez makes no pretext of

identifying Bolivar with Marxism, he does make a strong case for the endogenous,

national roots, of his ideology and practice. While supporting the Cuban revolution and

maintaining a close relation with Fidel Castro, he clearly makes no effort to assimilate or

copy the Cuban model even as he adapts to Venezuelan realities certain features of mass

organization.

Chavez economic practice includes extensive nationalization and expropriation

(with compensation) of large sectors of the petrol industry, selective nationalization of

key enterprises based on pragmatic political considerations including capital-labor

conflict (steel, cement, telecoms) and in pursuit of greater food security (land reform).

His political agenda includes the formation of a mass competitive socialist party within

the framework of a multi-party system and the convoking of free and open referendums

to secure constitutional reforms. The novelty is found in his encouraging of local self

government through the formation of non-sectarian communal councils based in the

neighborhoods to bypass the dead hand of an inefficient, hostile and corrupt bureaucracy.

Chavez’s goal appears, at times, to be the replacement of ‘representative’ electoral

politics run by the professional political class by a system of direct democracy based on

self-management, in factories and neighborhoods. In terms of social policy Chavez has

funded a plethora of programs designed to raise living standards of 60% of the population

that includes the working class, self-employed, poor, peasants and female heads of

households. These reforms include universal free medical care and education, up to and

including university enrollment. The contracting of over 20,000 Cuban doctors, dentists

and technicians and a massive program encompassing the building of clinics, hospitals

and mobile units criss-cross the entire countryside, with a priority to low income

neighborhoods ignored by previous capitalist regimes and private medical staffers. The

Chavez regime has built and financed a large network of publicly run supermarkets that

sell food and related household items at subsidized prices to low income families. In

foreign policy President Chavez has consistently opposed US wars in the Middle East

and South Asia, and the entire rationale for imperial wars embedded in the “War on

Terror” doctrine.

Critique: How Novel is Venezuela’s 21cs?

Several questions arise regarding the Venezuelan version of 21cs: (1) Is it really

“socialist” or better still does it represent a break with 20 century socialism in all of its

variants? (2) What is the ‘balance’ between past and existing capitalist features of the

economy and the socialist reforms introduced during the Chavez decade? (3) To what

degree have the social changes reduced inequalities and provided greater security for the

mass of the people in this transitional period.

Venezuela today is a mixed economy, with the private sector still predominant in

the banking, agricultural, commercial, foreign trade sector. Government ownership has

grown and national social priorities have dictated the allocation of oil resources. While

the mixed economy of Venezuela resembles the early post World War II social

democratic configurations in Europe, there is one key difference: the state owns the most

lucrative export sector and the principal earner of foreign exchange.

While the government has vastly increased social expenditures comparable or

exceeding spending in some of the earlier social democratic governments, it has not

reduced the great concentrations of wealth and income of the upper classes, via steep

progressive tax rates as in Scandinavia and elsewhere. Inequalities are still far greater

than existed under 20th century socialist societies and comparable to existing Latin

American societies. Moreover, the upper and upper middle levels of the state

bureaucracy especially in the oil and related industries have levels of remuneration which

are comparable to their capitalist counterparts, as was the case in nationalized industries

in England and France.

Self-management of public enterprises, a relative new idea in Venezuela , has

moved beyond the limits of German social democratic co-participation schemes but are

confined to less than a half-dozen major enterprises – a far cry from the extensive,

nationwide networks found in socialist Yugoslavia between the 1940’s – 1980’s.

The agrarian reform proposals of the Chavez regime though radical in intent and

forcibly promoted by President Chavez has failed to change the relationship between

farm workers, peasants and large landowners. Where inroads have been made in land

distribution, the government bureaucracy has failed to provide the extension services,

financing, infrastructure, and security to land reform beneficiaries.

The National Guard has by commission or omission failed to end landlord

assassinations of leaders and supporters of land reform by the hired guns of landlords.

Over 200 unsolved killing of peasants were on the books by the end of 2009.

While publicists of 21cs have emphasized the government’s nationalizations of oil

enterprises from existing owners, they have failed to take account of the growing number

of new joint ventures with multi-national corporations from China, Russia, Iran and the

European Union. In other words while the role of some US multi-nationals has declined,

foreign capital investment in mineral and petrol fields has actually increased especially in

the vast Orinoco tar fields. While the shift of investment partners in oil reduces

Venezuela’s strategic vulnerability to US pressure, it does not enhance the socialist

character of the economy. Joint ventures do add weight to the argument that Venezuela’s mixed public-private economy approximates the social democratic model of the mid 20th

century.

The most questionable aspect of Venezuela’s claim to socialism is its continued

dependence on a single commodity (oil) for 70% of its export earnings and its

dependence on a single market, the United States, an openly hostile and destabilizing

trading partner. The Chavez regimes efforts to diversify trading partners has taken on

greater urgency with Obama’s military pact with Columbian President Alviro Uribe, to

occupy 7 bases. Equally threatening to the mass base of the Chavez road to socialism is

the skyrocketing crime rate based on the growth of a lumpen-proletariat and its links to

Columbian drug traffickers and civilian and military officials. In many popular barrios

the lumpen compete with the leaders of the communal councils for hegemony, using

unrest and violence to exercise dominance. The ineffectiveness of the Ministry of

Interior and the police and their lack of a close working relation with neighborhood

organizations represent a serious weakness in mobilizing civil society and mark a

limitation in the effectiveness of the communal council movement.

The remarkable reforms instituted by the Chavez government, and the original

synthesis of Bolivarian emancipatory anti-colonialism, with Marxism and antiimperialism

mark a rupture with the predominant neo-liberal practice pervasive in Latin

America over the previous quarter century and still operative under numerous

contemporary regimes, who claim otherwise.

What is doubtful, however, is whether all the changes amount to a new version of

socialism given the predominance of capitalist property relations in strategic sectors of

the economy and the continuing class inequalities in both the private and public sector.

Yet one should keep in mind that socialism is not a static concept, but an ongoing

process, and the bulk of recent measures are tending to extend popular power in factories

and neighborhoods.

Ecuador

In Ecuador, President Correa has adopted the rhetoric of 21cs and it has gained

credibility in association with several foreign policy initiatives. These include the

termination of US military base lease in Manta; the questioning of parts of the foreign

debt incurred by previous regimes; the critique of Columbia’s border incursions and

military assault of a clandestine Columbian guerilla camp; his criticism of US free trade

policies and support of Venezuela’s regional integration program (ALBA). President

Correa has been identified as part of the ‘new wave of leftist Presidents’ by the mass

media including the NY Times, The Financial Times and numerous leftist journalists,

North and South.

In terms of domestic policy issues, President Correa’s claim to be a founding

member of 21cs rests on his critique of the traditional Rightist parties and the oligarchy.

In other words, his socialism is defined by what and who he opposes, rather than any social structural changes.

His main domestic achievements revolve around his denunciation of the major

electoral parties; his support for and leadership of a ‘citizens movement’, and its success in overthrowing the rightist US backed authoritarian electoral regime of Lucio Gutierrez,

the convoking of a constitutional assembly and the writing of a new constitution. These

legal and political transformations define the outer limits of Correa’s radicalism and

provide the substantive bases for his claim of being a 21cs. While these foreign policy

and domestic political changes, especially when taken in the context of increased social

expenditures during his first three years of office, warrant his being included as a “centerleftist”

they hardly suffice or add up to a socialist agenda especially if they are seen in the

large socio-economic structural matrix.

Critique of the Ecuadorian Practice of 21cs

The most striking departure of any credible claim to socialism is the persistence

and expansion of foreign private capitalist ownership of the strategic mining and energy

resources: fifty-seven percent of petrol is produced by overseas petroleum multinationals.

Large scale, long term mining contracts have been signed and renewed giving

foreign owned mineral companies’ majority control over the principal foreign exchange

and export earning sectors. What is worse, Correa has violently repressed and rejected

the long-standing claims of the Amazonian and Andean Indian communities living and

working on the lands signed off to the mineral multi-nationals. In rejecting negotiations,

Correa has dismissed the 4 major Indian movements and their allies in the ecology

movements as little more than a “handful of backward elements” or worse. The

contamination of waters, air and land leading to serious illnesses and deaths by the

foreign oil companies has been demonstrated in US courts where Texaco faces a billion

dollar law suit. Despite adverse court rulings, Correa has vigorously pursued his push to

make foreign led mineral exploitation the centerpiece of his “development strategy”.

While Correa has vigorously attacked the coastal financial agro-commercial

capitalist class, centered in Guayaquil, he has vigorously supported and subsidized the

Quito (Andean based) capitalist class. His “anti-oligarchy” rhetoric is certainly not anticapitalist

– as his embrace of 21cs would imply.

President Correa’s success in building a mass citizen electoral movement is

measured by his impressive electoral victories, securing presidential majorities under

multi-party competition, and over seventy percent in the constitutional elections. Despite

his popularity, Correa’s popular backing is largely based on short term concessions, in

the form of wage and salary increases and credit concessions to small business, measures

which are not sustainable with the onset of the world recession. His granting of

telecommunication monopolies to private firms, his opposition to land reform, and the

restrictions of trade union strikes, while not provoking systemic challenges have led to a

increasing number of strikes and protests. More important, the strengthening of capitalist,

especially foreign ownership, control of strategic banking, commercial export and

mineral sectors, reduces the claims of 21cs to a merely symbolic, rhetorical exercise.

What is apparent is that the basis for 21cs is rooted in foreign policy pronouncements

(which are subject to reversal) rather than changes in class relations, property ownership

and popular power. “21cs socialism”, in the case of Ecuador, appears as a convenient

way of combining innovative foreign policy measures with neo-liberal ‘modernization’

development strategies. Moreover, initial radical measures do not preclude subsequent

conservative backsliding as is evidenced in the questioning of the foreign debt (which

caused premature leftist ejaculations of glee) and subsequent return to full debt payments.

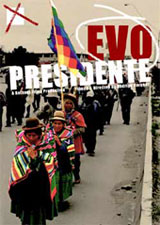

Bolivian Socialism White Capital, Indian Labor

The greatest contrast between 20th and 21st century “socialism” is found between

the current regime of Evo Morales (2005 - ) and the short lived Presidency of J. J. Torres

(1970-1971).

While the former has openly and publicly invited mineral and extractive multinational

companies from 5 continents to exploit gas, oil, copper, iron, lithium, zinc, tin,

gold, silver and a long list of other minerals, under the 20th century Torres regime, foreign

and local capitalist firms were nationalized, expropriated. While billions of profits are

currently repatriated both during and after the commodity boon; under Torres, state

control over capital flows and foreign trade limited the de-capitalization of the country.

While Evo Morales provides hundreds of millions in loans, export subsidies and tax

incentives to the wealthiest agro exporters and expels landless Indian squatters from large

estates, under President Torres land takeovers were encouraged as furthering the regimes

agrarian reform policies. There is an abundance of socio-economic data demonstrating

that the socialist polices undertaken during President Torres term of office stand in polar

opposition to the social liberal policies practiced by the Morales regime. In the following

sections we will outline the major social and liberal policies of the Morales regime in

order to assess the true meaning of the self-declared 21cs politics in Bolivia.

The Social Changes

Numerous social changes have been implemented by the Morales regime during

its first 5 years in power (2005 – 2009). The question is whether these changes add up to

any of the most generous definitions of socialism or even to transitional measures

pointing to socialism in the near or even distant future, given the scope and depth of the

liberal economic policies adopted.

Morales has implemented socio-political changes in nine policy areas. The most

significant domestic change is in the area political – cultural – legal rights of the

indigenous people. The regime has granted local governance rights for Indian

municipalities, recognized and promoted by-lingualism for carrying out local affairs and

education, given national importance to Indian religious and holiday celebrations and

promoted prosecution of those who violate or persecute Indian civil rights.

Under Morales the state has slightly increased its share of revenues in its joint

ventures with multi-national corporations, increased the price of gas sold to Brazil and

Argentina, while increasing the share going to the national government over and against

provincial governments. Given the record prices received by Bolivia’s agro-mineral

exports between 2005 – 2008, the local municipalities increased their revenue flow,

though actually investments in productive and service sectors lagged because of

bureaucratic bottlenecks.

Morales allowed for incremental increases in the minimum wage, salaries and

wages, thus marginally improving living conditions. The increases, however, were far

below Morales electoral promise to double the minimum wage and certainly not

comenserate with the large scale windfall profits resulting from the commodity boom.

Morales prosecution of local officials and the provincial governor of Pando

province and rightist terrorists for the assault and murder of Indian activists put an end to

impunity of white assaults on Indian citizens.

The regime’s biggest boast was the accumulation of foreign reserves from $2

billion to $6 billion dollars, fiscal discipline and strict control over social spending and

the favorable balance of payments. In this regard Morales’ practices were more in line

with the IMF than anything remotely resembling the expansive economic practices of

socialist and social democratic regimes.

Tripling reserves in the face of continued 60% poverty levels for the mostly rural

Indian population is a novel policy for any regime claiming socialist credentials. Even

contemporary capitalist, North American and EU regimes have not been as orthodox as

the Morales’ political cultural revolutionary regime.

Morales has promoted trade union organizations and mostly avoided repression of

miners and peasant movements, but at the same time has co-opted their leaders, thus

lessening the number of strikes and independent class action, despite the continued

inequalities in the society. De facto greater tolerance is matched by the increased

‘corporatist’ relation between regime and the popular sectors of civil society.

Morales economic strategy is based on a triple alliance between agro-mineral

multi-nationals, small and medium size capitalists and the Indian and trade union

movements. Morales has poured millions in subsidies to so-called “cooperatives” which

are in reality private small and medium size mine owners who exploit wage labor at or

below standard wages of miners in larger operations.

The principle changes under the Morales regime are in its foreign policy and

rhetoric. Morales has aligned with Venezuela in supporting Cuba, joining ALBA,

developing ties with Iran, and above all, opposing US policy in several important areas.

Bolivia opposes the US embargo against Cuba, the seven military bases in Columbia, the

coup in Honduras and its lifting of tariff preferences. Equally important Bolivia has

terminated the presence of the US DEA and curtailed some of the activities of AID for

subsidizing right wing socio-political organizations and destabilization activity. Morales

has spoken out forcefully against the US wars in Afghanistan, and Iraq, condemned

Israel’s assaults against the Palestinians and has been a consistent supporter of nonintervention,

except in the case of Haiti, where Morales continues to dispatch troops.

Critique of Bolivia’s Version of 21cs

The most striking aspect of Bolivia’s economic policy is the increased size and

scope of foreign owned multinational corporate (MNC) extractive capital investments.

Close to a hundred MNC are currently exploiting Bolivia’s mineral and energy resources,

under very lucrative conditions, including low wages, and weak environmental

regulations. Moreover, in a speech in Madrid (September 2009) Morales told an

audience of elite bankers and investors that they were welcome to invest as long as they

didn’t intervene in politics and agreed to joint ownership. Whatever the merits of

Bolivia’s foreign capital driven mineral export strategies, (and the historical record is not

encouraging), it puts a peculiar twist on “21cs”: replacing proletarian and peasants with overseas CEO’s and local technocrats: a novel way to practice “socialism” in any century

but more fittingly associated with free market capitalism.

In line with Morales “open door” policy toward extractive capital, he has

strengthened and provided generous subsidies and low interest loans to the agro-business

sector, even in those provinces like the “media luna” where ‘big agro’ has backed

extreme rightist politicians destabilizing his regime. Morales willingness to overlook the

political hostility of the agro-business elite and to finance their expansion is a clear

indication of the high priority which he gives to orthodox capitalist growth over and

above any concern with developing an alternative development pole built around

peasants and landless rural workers.

On site visits to rural areas and urban slums, reinforce published reports about the

unchanged nature of class inequalities. The super rich 100 families of Santa Cruz

continue to own over 80% of the fertile lands and over 80% of the peasants and rural

Indians are below the poverty line. Mine ownership, retail and wholesale trade, banking

and credit continues concentrated in an oligarchy which has in recent years diversified its

portfolio across economic sectors, creating a more integrated ruling class with greater

links with global capitalist actors.

Morales has fulfilled his promise to protect and secure the traditional multi-sector

economic elite, but he has also added and promoted new private and bureaucratic

entrants, to the ruling class, mainly foreign CEO’s and high paid functionaries directing

public private partnership.

While most socialists (of any century) would agree that big landowners are hardly

the building blocks to a socialist transition, Morales has in fact depended upon and

promoted agro-export production over family farming for local food production. Even

worse the conditions of farm workers has barely improved; in extreme cases several

thousand Indians were still exploited via slave labor, into and beyond the third year of

Morales administration. The harsh exploitation of farm laborers is far lessar concern than

the increase of productivity, exports, and state revenues to the regime. While labor

legislation facilitating labor activity has been approved, it has not been enforced in the

countryside especially in the ‘media luna’ provinces, where labor inspectors avoid any

confrontations with well entrenched landowner associations. The few land occupations

by the landless rural workers have been denounced by the government. Any grass roots

movements pressing for land reform in extensive under cultivated estates have been

strongly opposed by the government, violating its own norms that only cultivated farms

would not be expropriated.

Given the regimes emphasis on the “cultural and political” aspects of its version

of 21cs it is not surprising that it has spent more time and funds celebrating Indian fiestas,

song and dances, than it has in expropriating and distributing fertile lands to the

malnourished mass of Indians.

The regime’s effort to deflect attention from agrarian reform, by settling landless

Indians on public lands in distant tropics was a disaster. This “colonization plan”

organized by the so-called agrarian reform institute, dumped highland Indians in disease

ridden lands which were not cleared, without farm tools, seeds, fertilizers and even living

quarters. Needless to say in less than two weeks the Indians demanded bus transportation back to their impoverished villages, an improvement over these remote malaria ridden ill

planned settlements. To compensate for the lack of any comprehensive land

redistribution program, Evo Morales occasionally organizes, with pomp, ceremony and

much publicity, “gifts” of tractors to middle and small scale farmers, more a political

patronage opportunity rather than an integral part of a social transformation.

The two most striking aspects of Morales economic and political strategies is the

emphasis on the traditional extractive mineral exports and the construction of a typical

corporatist-patronage based electoral machine.

Into the fifth year of his regime the joint ventures signed with foreign MNC have

extracted and exported raw materials with a little of value added. To an astonishing

degree there has been a minimal degree of industrialization and final product manufacture

which would generate greater industrial employment. The same story is true of

agricultural exports – most grains and other agricultural products are not processed in

Bolivia, which would provide thousands of jobs for the poverty stricken mass of landless

Indians. The regime has accumulated huge reserves, but has failed to finance or foment

local industry to substitute for imports of capital, intermediate and durable consumer

imports.

Morales political strategy closely resembles that adopted by the Nationalist

Revolutionary Movement (MNR) a half century ago, in which trade unions and

especially peasant movements were incorporated to the dominant party – state. In the

absence of significant socio-economic changes, the government has relied on public

patronage, channeled through trade union and peasant and Indian leaders, which trickles

down in the form of local favors for party loyalists. Morales style clientelism is

constantly reinforced by the symbolic gestures re-affirming the “Indian” ethnic identity

and “solidarity” between the giver and recipient of political patronage.

The 21cs of Morales’ political practice is far less innovative and ’socialist’ and far

closer in political style to 20th century corporatist predecessors. Observers with little

knowledge of Bolivia’s past, impressionistic journalists enamored with symbolic politics

and financial writers who pin the “socialist label” indiscriminately on politicians who

even rhetorically question the free market doctrine, have reinforced the ‘radical’ or 21cs

image of the Morales regime. Given what we have described about the real practices of

the 21cs regimes it is useful to place them in a broader historical-comparative framework

to make some sense of their possible impact on Latin American society.

Comparative-Historical Analyses of 3 Cases of 21 Century Socialism:

Despite claims by regime publicists, the most striking aspect of 21cs regimes is

what is not novel or special about their policies. Their adoption of a mixed economy and

playing politics according to the institutional rules of a liberal capitalist state, differs little

from the practices of European Social Democratic parties of the late 1940’s to the mid

1970’s. To the degree that the 21cs pursue nationalist politics (and we should note that

nationalization means expropriatism and public ownership) they are a pale reflection of

the measures taken between the 1930’s – mid 1970’s. With the exception of the Chavez

regime, the rest of what passes as 21cs has at best nationalized bankrupt private firms,

increased shares in joint ventures and raised taxes on agro-mineral exporters.

The ‘indigenismo’ most forcefully expressed by two Andean regimes, Bolivia and

Ecuador, resonated with the rhetoric of the ‘indo-americanismo’ of the 1930’s. This was

forcefully pronounced by Peruvian Marxist writer Mariatagui and APRA political leader

Haya de la Torre, as well as the Chilean Socialist Party, a number of Bolivian and

Mexican writers, Augusto Sandino the Nicaraguan guerilla leader, and the revolutionary

El Salvadorean leader Farabundo Marti. In striking contrast to the 21cs indigenistas,

their predecessors in Central America, pursued profound agrarian reforms, including the

restoration of millions of acres of confiscated fertile lands and a profound rejection of

the agro-business export model. The earlier version of indigenismo combined symbolic

identification with deep substantive changes in contrast to the contemporary indigenistas

who rely mostly on symbolic gestures and identity politics.

The current policies relying on joint ventures resonates with the reformist

alternatives to the Cuban revolution, which found expression in JF Kennedy’s Alliance

for Progress, which was taken up by the Christian and Social Democratic counterinsurgency

regimes of the 1960’s. In opposition to the 20th century socialists and

communists who favored the socialization of the economy, the Chilean Christian

Democratic government (1964-70) promoted an alternative “Chileanization”, which

resembles Evo Morales and Correa’s “joint ventures”. In other words the economic

model of 21cs is far closer to the anti-socialist US backed reformist model of the 1960’s

than to any socialist variant of the past.

21cs and 20 th Century Social Democracy

While the scope and depth of socio-economic changes pursued by 21cs does not

approximate the structural changes of 20cs regime, how does it measure up to the

reformist or social democratic variant?

Three cases of social democratic regimes based on electoral politics come to

mind: the Arbenz regime in Guatemala (1952-4); the Goulart regime in Brazil (1962-64)

and the Allende regime in Chile (1970-73). All 3 past social democratic regimes pursued

agrarcan reforms of greater impact, with thousands of peasant beneficiaries, than the

contemporary 21cs. More substantial real nationalizations of foreign firms took place

than in two of the - three contemporary 21cs social democratic regimes (Venezuela has

expropriated a comparable number of firms).

In terms of foreign policy pronouncements and practices the anti-imperialist

political rhetoric is similar, but the earlier social democrats were more likely to

expropriate foreign capital. For example Arbenz expropriated land from United Fruit,

Goulart nationalised ITT and Allende expropriated Anaconda copper. In contrast our

21cs have promoted and invited foreign agro-businesses and MNC mining corporations

to exploit land and mineral resources. The different foreign economic policies

correspond to the different internal class composition and economic alignments between

20th and 21st century social democracy. In contrast to conventional misconceptions, the

21cs have consummated pacts between regime technocrats, the multi-nationals, and

domestic agro-mineral elites which weigh far heavier in decision making centers, than the

mass electoral base of Indians and workers. In contrast the peasant and worker

movements had greater representation and independence of action within and without the

20th century social democratic regimes.

21cs Defining a New Historical Configuration or a Cyclical Political Process?

An examination of Latin American’s past 60 years of history reveals a consistent

cyclical pattern of alternating left and right ‘waves’ of political regimes. The underlying

‘constant’ has been the struggle between, on the one hand US imperialist projections of

power either through direction intervention, military dictatorships and client civillians

regimes and on the other hand, popular democratic and socialist movements and regimes.

The question of whether the latest wave of “center-left” regimes is simply the latest

expression of this cyclical pattern or whether basic alterations in the underlying internal

and external structural relations are operating to provide a more sustainable process? We

will proceed to outline the past cyclical pattern of left/right politics in the past and follow

with a discussion of some key contemporary global and regional changes which might

lead to greater sustainability for left political hegemony.

Post WWII Latin American history has experienced roughly 5 cycles of left/right

predominance. The immediate period after WW II, following the defeat of fascism,

witnessed the world wide advance of democracy, anti-colonialism and socialist

revolutions. Latin America was no exception. Center-left social democratic, nationalist

populist, popular front governments took power in Chile, Argentina, Venezuela, Costa

Rica, Guatemala, Brazil and Bolivia between 1945-52. Juan and Eva Peron nationalized

the railroads, legislated one of the most advanced welfare programs and elaborated a

regional “third way” foreign policy, independent of the US. A coalition of socialists,

communists and radicals won the 1947 election in Chile on the promise of extensive

labor and social reforms. In Costa Rica a political upheaval dismantled the national army.

In Venezuela a social democratic party (Accion Democratica) promised to extend public

control over petroleum resources and increase tax revenues. In Guatemala, newly elected

President Arbenz expropriated uncultivated fields of the United Fruit Company,

implemented far reaching labor legislation promoting the growth of unionization and

ended debt peonage of Indians.

In Bolivia a social revolution resulted in the nationalization of the tin mines, a

profound agrarian reform, the destruction of the army and the formation of workers and

peasant militia. In Brazil Getulio Vargas promoted state ownership, a mixed economy

and national industrialization.

The launching of the Truman doctrine in the late 1940’s, the US invasion of

Korea (1950), the aggressive pursuit of the Cold war entailed vigorous US intervention

against democratic left of center and nationalist regimes in Latin America. Given the

green light in Washington, the Latin American oligarchies and US corporate interests

backed a series of military coups and dictatorships throughout the 1950’s. In Peru

General Odria seized power; Perez Jimenez seized power in Venezuela; General Castillo

Armas was put in power by the CIA in Guatemala; elected President Peron was

overthrown by the Argentine military in 1955; Brazilian President Vargas was driven to

suicide. The US succeeded in forcing the break-up of the popular front and the outlawing

of the Communist Part in Chile. The US backed Batista’s coup in Cuba, the Duvaeier

and Trujillo dictatorships in Haiti and the Dominican Republic. The rise of the extreme

right, the overthrow of center-left regimes and the bloody repression of trade unions and

peasant movements, secured US hegemony, assured conformity with US Cold war

policies and opened the door wide for a corporate economic invasion.

By the end of the 1950s the very extremities of US domination and exploitation,

the brutal repression of all democratic social movements and left parties and the

oligarchies pillage of the public treasury led to popular upheavals and the return of leftist

hegemony.

Between 1959 through 1976, leftist regimes ruled or challenged for power

throughout the continent with varying degrees of success and duration. The social

revolution in Cuba in 1959 and a political revolution in Venezuela in 1958, was followed

by the election of nationalist populist regimes of Jango Goulart in Brazil (1962-64), Juan

Bosch, (1963) reinstated for a brief moment in (1965), Salvador Allende in Chile (1970-

73), and Peron in Argentina (1973-75). Progressive nationalist – populist military rulers

took power in Peru (Velasco), 1968, Rodriquez in Ecuador (1970), Ovando (1968) and J.

J. Torrs (1970) in Bolivia, Torrijos in Panama. All challenged US hegemony to one

degree or another. All were backed by mass popular movements, clamoring for radical

socio-economic reforms. Some regimes nationalized strategic economic sectors and

implemented far-reaching anti-capitalist measures.

However, all but the Cuban revolution had a short life span. Even in the midst of

the 1960’s – 70’s left turn, the US and its military clients intervened vigorously to revert

the prospect of progressive social changes. Brazil’s Goulart fell to a US backed military

coup (1964); preceded by Juan Bosch (1963) and followed by the US military invasion

against the restorationist revolution of 1965/66; a US backed military coup in Bolivia

overthrew Torres in 1971; Chile’s Allende was overthrown by a joint CIA – military

coup in 1973; followed by Peru’s Velasco(1974) and Argentina’s Peron, 1976. The

promising and deep going leftist wave was over for most of the duration of the 20th

century.

Between 1976 – 2000, with the notable exception of the victory of the Sandinista

revolution in 1979, the right was in ascendancy. Its long rule secure through the worst

continent wide repression in the history of Latin America. The military regimes and the

subsequent authoritarian neo-liberal civilian electoral regimes dismantled all tariffs and

capital controls in a wild plunge into the most extreme and damaging free-market,

imperial centered economic policies. Between 1976 – 2000 over five thousand public

firms were privatized and most were taken over by foreign multi-nationals; over a trillion

and a half dollars were transferred overseas via profits, royalties, interest payments,

pillage of public treasuries, tax evasion and money laundering. However, the ‘golden

era’ for US capital during the 1990s was a period of economic stagnation, social

polarization and growing vulnerability to crises. The stage was set for the popular revolts

of the early years of the new millennium and rise of the latest wave of center-left regimes

in the region, which brings us back to the question of the sustainability of this new wave

of leftist regimes.

Some World Historical Structural Changes

One of the key factors reversing past leftist waves in Latin America was the

economic power and interventionary capacity of the US.

There is strong evidence that US power has suffered a relative decline on both

counts. The US is no longer a creditor country; it is no longer the leading trading partner

with Brazil, Chile, Peru and Argentina and is losing ground in the rest of Latin America,

except for Mexico. Washington has lost influence even in it “patio”, the Caribbean and

Central America, where several countries have signed up for the Venezuelan subsidized

petroleum agreement (Petrocaribe). Washington, as if to compensate for its lost of

economic leverage, (highlighted by the rejection of its proposed Latin American Free

Trade Agreement) has increased its military presence, by expanding 7 military bases in

Columbia, backing a coup in Honduras against a social liberal president and increased the

presence of the Fourth Fleet off Latin America’s coast. Despite the “projection of

military” power, circumstances outside of Latin America have weakened US

interventionary capacity, namely the prolonged costly unending wars in Iraq,

Afghanistan, Pakistan and the military confrontation with Iran. The already high levels

of public exhaustion and opposition, makes it difficult for Washington to launch fourth

war in Latin America. Therefore, it relies on and finances local client military – civilian

power configurations to destabilize and overthrow center-left adversaries. The increase

in global markets, especially in Asia, has allowed Latin regimes to diversify their markets

and investment partners, which limits the role of US MNC and limits their possible

political role as purveyors of State Department policies. The financialization of the US

economy, has eroded the US industrial base and limited its demand for agro-mineral

export products from Latin America, shifting the latter’s dependence on new emerging

powers. Moreover having suffered the consequence of financial crises, Latin regimes

have imposed some regulations on capital movements, which limits the operation of US

investment bank speculators, prime movers in the US economy. While Washington talks

“free markets” its application of protectionist measures (on overseas leading) and

subsidies to agriculture (sugar, ethanol) have antagonized key Latin American countries

like Brazil. As the leading exponent of failed free market neo-liberal doctrine, the US

has suffered a major loss of ideological influence in the region as a consequence of the

global recession of 2007 – 2010.

For these reasons, one of the major actors (US imperialism) which has been

responsible for the cyclical rise and fall of leftist regimes, has been structurally

weakened, improving the chances for longer duration. Yet, the US is still a major factor

acting with potent resources based on its close ties with major rightist military and

economic forces in the region. Secondly, by the very nature of the development

strategies chosen by the ‘center-left regimes’ they are very vulnerable to crises – namely

the agro-mineral export policies based on foreign and domestic economic elites and

fluctuating world demand. Thirdly, the center-left regimes have failed to resolve basic

regional imbalances, to significantly lessen social inequalities and to recapture

ownership and control of strategic economic sectors. These considerations call into

question the middle term durability of contemporary center – left regimes.

There are few internal changes in the nature of the state apparatus and class

structure which could prevent a reversion back to neo-liberal policies. The basic question

of whether the current 21cs regimes are stepping stones toward further socialization or

simply transitory regimes opening the way for a restoration of neo-liberal pro – US

regions, is still open to dispute, even as evidence is accumulating that the latter outcome

is more likely than the former.

Conclusion

The question of whether 21cs is better or worse than 20th cs depends on what

versions of each we choose to compare and what political dimensions we select in our

comparative evaluation.

First and foremost there is no single ’model’ of 20th century socialism, despite the

facile equation of 20th century socialism with the Soviet variant. There were essentially

four radically different types of 20th century socialist regimes, which in turn were

internally varied.

(1) Revolutionary single party regimes, which includes Cuba, North Korea,

China, Vietnam and the USSR. The first four combined socialist and national

liberation struggles and were consummated independently of the USSR and

exhibited at different times greater and lesser degree of openness to debate

and individual freedoms. The ‘four’ all fought US invasions and were all

subject to embargos and under intense destabilization campaigns requiring

high level of security measures.

(2) Electoral revolutionary socialist regimes include Chile (1970 – 73), Grenada

(1981 - 33), Guyana (1950’s), Bolivia (1970 – 71) and Nicaragua (1979 – 89).

Multi-party competition and the four freedoms were encouraged even at the

expense of national security. All were subject to successful US backed

military intervention, military coups and economic embargoes.

(3) Self-managed socialism was put in practice in Yugoslavia factories from the

late 1940s to the mid 1980s and was briefly experimented in Algeria between

1963-64. US and European promoted separatist movements dissolved the

Yugoslavia state and a military coup ended the Algerian experiment.

(4) Social democracy based on large scale, long term social welfare program

linked to state management of macro-economic policy was implemented in

the Scandinavian countries, especially Sweden.

The stereotype of the Soviet model of externally imposed authoritarian socialism was

applicable only to Eastern Europe; even that was subject to changes and democratic

moments such as 1968 in Czechoslovakia and Hungary in the 1980s.

Likewise there are significant variations among 21cs socialists.

Venezuela has nationalized major foreign and nationally owned enterprises (oil, steel,

cement, banking, telecoms) expropriated large tracts of farmland and settled over 100,000

families, financed universal public health and educational programs and encouraged

community councils and worker self-management in a few instances.

Bolivia has expropriated few if any major firms. Instead Morales has promoted

and signed public-private joint ventures, opened the door to dozens of foreign mining

consortiums, supported political reform enhancing and extending civil rights to Indians

and increased social expenditures for housing, infrastructure and poverty alleviation. No

agrarian reform has taken place and none is foreseen.

The third and most conservative variant of 21cs is found in Ecuador, where major

concessions to mining and petroleum companies is accompanied by the privatization of

telecom concessions and subsidies to regional business elites. Rather than land reform,

Correa has transferred Indian lands to mining companies for exploitation. Major claims

to socialism are found in increased levels of social expenditures, the revoking of US use

of a military base in Manta and a general criticism of US military and free trade policies.

Correa retained the dollarized economy, limiting any expansionary fiscal policies.

By drawing on commonly agreed criteria for evaluating the socialist nature of

both 20th and 21st century socialism we can form an informed judgment on their

performance in achieving greater economic independence, social justice and political

freedom.

Public Ownership

All variants of 20th century socialism – except the Scandinavian model – achieved

greater public control over the commanding heights of the economy than their 21st

century counterparts. Venezuela is the closest approximation of the 20th century

experience. The comparative performance of the public, public-private and private

models varies: in terms of growth and productivity, the public enterprises in the 20th

century have a mixed record, of high growth tailing off to stagnation; the mixed

enterprises are subject to the vagaries of the market and world demand, alternating

between high growth in times of boom and depressed output in times of low commodity

prices.

In terms of social relations, the social benefits and work conditions in the public

sector socialism are generally more generous than in mixed and privately owned

industries, though wage remuneration may be higher in the latter.

Agrarian Reform

The 20cs were far more successful in redistributing land and breaking the power

of the landlord class than any measures applied by the 21cs. The redistributive reforms

of the 20cs contrast with the agro-export strategies by most contemporary ‘21cs’ who

have actually promoted greater concentration of landownership and inequality between

agro-business elites and peasants and rural landless workers. The agrarian reforms,

however, were poorly managed, especially in the case of Cuba and China and led to a

second transformation, redistributing state farms to family farmers and cooperatives.

On the whole 20th century socialists were much more successful in reducing

inequalities of income (but not eliminating them) than their contemporary counterparts.

Because 21st century capitalists, especially big mine owners, agro-business capitalists and

bankers, still control the commanding heights of the economies, the historic inequalities

between the top five percent and the bottom sixty percent remain unchanged.

In terms of social welfare, 21st century socialist have increased social spending, raised the

minimum wage but with the notable exception of Venezuela, do not match the universal free

public health and educational programs financed by the 20th century socialism.

While there were regional imbalances between the countryside and the city under 20th

century socialism; free medical care, social security and basic health care was available to the

rural poor under 20cs and is still lacking in most 21cs regimes.

In terms of anti-imperialist struggles the record of 20th century is far superior to that of

the 21cs. For example, Cuba sent troops and military aid to Southern Africa (especially Angola)

to repulse an invasion by the racist South African regime. China sent troops in solidarity with

Korea and secured the north half region from the US invading army. The USSR provided

essential arms and air defense missiles in support of the Vietnamese national liberation struggle

and provided Cuba with almost a half decade of economic subsidies and military aid allowing it

to survive the US embargo.

Today’s 21cs with the partial exception of Venezuela have provided no material support

for ongoing liberation struggles. On the contrary, Brazil, Bolivia, Chile and Argentina continue

to provide military forces in support of the US sponsored occupation of Haiti. At best the 21cs

condemn the US backed coup in Honduras (2009), Venezuela (2002) and military bases in

Ecuador and Columbia and reject a US centered free trade agreement.

The one area in which the 21cs have an apparent advantage is in the promotion of greater

individual freedoms and electoral processes. There is greater tolerance of public debate,

competitive elections and political parties than was allowed in some variants of 21cs.

None the less economic democracy, or workers power was far more advanced in 20th

century Chilean socialism and Yugoslavian self-management than is the case of 21cs

parliamentary elections. Moreover, in the past there was greater concern for workers’ opinions in

making policy even in the authoritarian systems than takes place in the current agro-mineral 21cs

states. The greater openness of 21cs is related to the fact that they face less high intensity

military threats. In part this is because they have not altered the basically capitalist nature of their

economics.

In comparison with 20cs, the 21cs are generally more conservative, work closer with

MNC are less consistently anti-imperialist and are based on multi-class coalitions that span the

class hierarchy, linking the impoverished poor sectors of the middle class to the very powerful

agro-mineral elites. Though 21cs may occasionally make reference to class analysis, in times of

crises their operative concepts obscure class divisions through the use vague non-specific’

populist’ categories.

Perhaps the radical image of the 21cs results from their contrast with the previous

extremist rightwing regimes which ruled during the previous quarter century. The socialist label

pinned on contemporary regime by Washington and the western media represents a nostalgia for

a past of unfettered political submission, unregulated economic pillage, and robust repression of

popular movements rather than an empirical analysis of their socio-economic policies.

Even as the 21cs are less radical and perhaps distant from commonly accepted definitions

of socialist politics, they still have drawn the line in opposition to US militarism and

interventionism, have put a cap on control over natural resources and provide greater tolerance

for the organization of social movements.

Articles by this author

Articles by this author Send a message

Send a message

Stay In Touch

Follow us on social networks

Subscribe to weekly newsletter