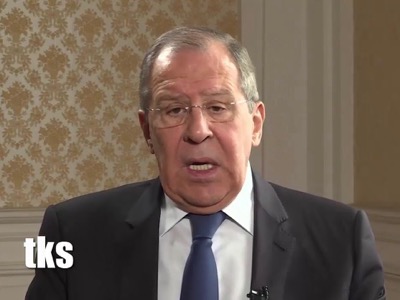

Sergey Lavrov’s interview for a Vladimir Kobyakov documentary, “A U-Turn over the Atlantic”

Question: Mr Lavrov, the bombing of Yugoslavia was carried out 20 years ago. What were, in your opinion, the main geopolitical reasons why the United States launched this large-scale military operation?

Sergey Lavrov: As I see it, it was the beginning of the period when Washington decided that they had won the Cold War. The Soviet Union had disappeared, Russia was weak and sought to convince everyone that it wanted to join the Western democratic processes and become part of the civilised world, as the Russian leaders of the time said. Obviously, they thought we were uncivilised in the Soviet era. But Washington felt tempted to take the situation in the entire world under its full control, to abandon the principles of coordinating approaches to international problems based on the UN Charter, and to address all arising issues in such a manner as to dominate in all regions of the world. It goes without saying that the Yugoslav story also had to do with the desire to promote NATO’s eastward expansion closer to the Russian Federation’s borders. There is no doubt about that. The subsequent developments prove this to be generally the case.

Question: How was this accepted in Moscow at the time? Wasn’t the political elite split down the middle? Did you feel that we could enter into a military confrontation with NATO on this account?

Sergey Lavrov: No. At that moment, we were discussing, including at the UN, the possibility of sending a peacekeeping mission to prevent clashes and reduce tensions around Kosovo. The West, primarily the United States, was categorically against this.

Question: Why didn’t they want our peacekeepers?

Sergey Lavrov: Because they wanted to address the issues on their own. They were not interested in reducing tensions. They needed a situation where Yugoslavia would break up. By that time, Yugoslavia had already disintegrated, but obviously not until the end, the end that the West desired. The Kosovo gamble was aimed precisely at this. In the end, we had a paratroopers contingent on the ground that had entered the territory at our initiative, in line with a decision by the Russian leadership, rather than in the context of some grand international peacekeeping mission. I remember well how the Western representatives grew pensive when it took the Slatina airport under its control. Thank God, the hotheads in Washington and other capitals, specifically London, who were urging that the Russians be reined in, did not prevail. What did prevail was the professionalism of the Western military, including British soldiers, who were deployed on the ground. There was an incident where our contingent had a close encounter with the British but, I repeat, the top professionalism of the military on both sides prevailed.

Question: Yes, that was really something.

Sergey Lavrov: It could have been very bad indeed. I repeat, the military acted to the best of their abilities.

Question: Let’s go back to early 1999. In her memoirs, Madeleine Albright writes that “Serbs out, NATO in, refugees back” became the US diplomats’ mantra in January 1999. Do you think Russian diplomats had any other options that they had not used to convince Washington to renounce the idea of air strikes?

Sergey Lavrov: Ms Albright personally phoned all the ministers of NATO member countries, persuading them, urging them and even forcing some of them to support the air strikes. Greece became the only NATO country that did not take part in this reckless undertaking and which denounced it.

Regarding the opportunities for averting this disaster, we did everything in our power. An OSCE mission was established largely on our initiative; it was deployed in Kosovo, for the most part, and also in adjacent areas. In early 1999, a conference went on for several weeks in Rambouillet near Paris, where the Americans tried to railroad President of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Slobodan Milosevic with their ultimatum, to persuade him to resign and to cede power to some unspecified person. They tried to formalise that ultimatum as a demand of the entire international community. We prevented them from using the Rambouillet conference for these purposes and defended the norms of international law that called for resolving any disputes by peaceful methods. Of course, they later did the same at the UN Security Council.

Question: You were working there at that time. What did people say behind the scenes?

Sergey Lavrov: It wasn’t just behind the scenes activities: meetings and public discussions also took place. It goes without saying that all Western countries, permanent members of the UN Security Council, namely, the United States, the United Kingdom and France, staunchly advocated the use of force. They were supported by the then rotating UN Security Council members, Canada and the Netherlands. Russia, China and two other rotating UN Security Council members, Argentina and Brazil, vehemently opposed this scenario and the demands to either use force or approve the use of force.

You know how it ended. It was no longer possible to stop the Americans. They made their decision long ago and tried to formalise it at the UN Security Council. After realising that their plans failed, the Americans launched a unilateral aggression against a sovereign state in violation of the UN Charter, principles of the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe and the entire world order that was established after World War II.

This trend also continues to manifest itself today. At that time, the process of replacing various concepts got underway, and the Americans moved to wreck international law and to replace it with certain rules for maintaining this order. Today, instead of advocating compliance with international law, Western countries are increasingly using the concept of “rules-based order.” The difference is clear: international law is the result of consensus-based talks, whereas the rules are invented by the West itself, which then demands that everyone else follow them. All this began at the time we are talking about, 20 years ago.

Question: The then pretext for a war, for punishing the Serbs, was the Račak massacre. At least this was what US diplomats were saying.

Sergey Lavrov: This was not a pretext but an artificially created excuse. That it was a provocation was known all along. People spoke and wrote about it, and provided evidence time and again. The victims, allegedly peaceful civilians, were in fact Albanian Liberation Army fighters, I mean the so-called Kosovo Liberation Army, who had been disguised as civilians. It has long been known that it was a “frame-up.” Regrettably, this provocation was arranged by an American, William Walker, the then head of the OSCE mission, who arrived on the scene of the event, found the bodies that, as I say, were neatly disguised as civilians, and said right there on the spot that an act of genocide had been committed. Regardless of what he saw – and he saw a provocative stitch-up – he had no right, in terms of his powers, to make such a declaration. It was only the OSCE Permanent Council, to which he was accountable and obliged to report, that had the authority to draw conclusions about what was going on. By and large, he played the same role as the so-called White Helmets are playing in Syria today by constantly staging fake incidents that give the West a pretext for launching attacks on a sovereign state.

Question: There was a report with an expert analysis by Finnish forensic experts. You were attempting to gain access to it. Was it lost or classified?

Sergey Lavrov: With support from many of my colleagues, I urged the UN Security Council to have this report published. Regrettably, it was not provided to us in full. The former prosecutor of the International Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, Carla Del Ponte, circulated in the UN Security Council a maximally cleaned-up summary that on the whole sounded neutral. But the full text was never provided.

Question: In the early 2000s, the International Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in The Hague made an attempt to bring charges against the NATO command for civilian deaths, attacks on civilian facilities and the use of munitions with [depleted] uranium. At that time, this mechanism faltered. Is there any hope that an international investigation will be resumed?

Sergey Lavrov: I think the West has done and will continue to do all it can to prevent this from happening.

As for the banned munitions, the Serbs have been conducting an investigation of their own. As soon as we have the results, we will see what can be done so as not to leave this crime unpunished. To reiterate: I see practically no chance of this being approved by the international institutions, where the West is present and where Western votes are counted. They will do their best to prevent this from happening.

Let me give you an example. In 2010, a Swiss MP, Dick Marty, published a report exposing monstrous crimes committed by the Kosovo Liberation Army thugs, who kidnapped people and used them for illegal trafficking in human organs. With the report on the table, we did not allow this problem to be swept under the carpet. A high-profile campaign was launched that called for an investigation and punishment for those who had committed these crimes. After protracted disputes and altercations, the West had to agree to make the Kosovo government give its consent to establishing a special court to investigate the crimes described in the Marty report. Formally, the court was created but it has been out of business for several years. A prosecutor, a US citizen by the way, was appointed. The Americans did their best to have this post fall to a US citizen. Two prosecutors have been replaced since then, with a third one (again an American) filling the position now. But no charges have been brought. I even doubt that the investigation is proceeding in any coherent way. So, the West will hush up the facts that lay open the crimes against humanity committed by itself and its charges.

The operation itself, when they were bombing Serbia, was carried out with gross violations of all principles of international humanitarian law, because they were bombing purely civilian facilities. For example, there is a case on record, where NATO aircraft attacked a passenger train that was passing across a bridge. And it was an absolute outrage when they bombed the TV Centre. Today we hear the echoes of that attack in situations where claims are made that certain media are “propaganda tools” rather than sources of information. This is how, incidentally, RT and Sputnik are branded in France. Their correspondents are banned from public events, where other media are accredited. It was then that a number of media outlets took to accusing journalists of being “propaganda mouthpieces,” a claim that explained the reason why the TV Centre in Belgrade had to be attacked.

Question: But the Chinese Embassy was also hit in that attack…

Sergey Lavrov: I think it was some error, but I am not quite sure.

Question: How did the 1999 bombing of Yugoslavia influence further developments in international politics?

Sergey Lavrov: By and large, it did not teach the West anything, if, of course, it wanted to learn, which I doubt. If they learned a lesson after all, it was a negative one, because soon after 1999, in 2003, a decision was taken to invade Iraq under a far-fetched pretext that Iraq possessed chemical and biological weapons. As for nuclear weapons, there were also attempts to call into question the report that confirmed the absence of these weapons in Iraq. Here is an aggression against yet another sovereign country. The country is in tatters. Currently, it is being pieced together with great difficulty, but problems remain. Several hundred thousand people have been killed since 2003; there is no doubt about that.

After that, in 2008, the West, following the same line and in a bid to justify its aggression against Yugoslavia, recognised unilaterally Kosovo’s independence, although there was no reason whatsoever for disrupting the UN-sponsored negotiations between Belgrade and Pristina. There were no attacks from either side, and the West’s claims that they had to unilaterally recognise Kosovo’s independence because the Albanians in Kosovo were threatened by the Serbs, were absolutely far-fetched and groundless. The line for undermining international law persisted into 2011, when NATO carried out an aggression against Libya after grossly distorting a UN Security Council resolution. In this case, the country ended up in ruins the way Iraq had, and it is still a tall order to piece it together, because there are too many problems.

All these gambles resulted, among other things, in an unprecedented surge of international terrorism, organised crime and illegal migration…

Question: Do you mean Kosovo?

Sergey Lavrov: No, I am talking about the results of all these gambles, including in the Middle East. Kosovo is being ruled by the people who care nothing about even the timid advice, which the West is attempting to offer, on the need to normalise relations with Belgrade. The EU has been trying to act as a mediator for years. But Pristina ignores all agreements that in some way or other, as a first step, were aimed at guaranteeing the Serbs’ rights in Kosovo. In response, the EU displays absolute helplessness.

A few days ago, in early March, Pristina published its negotiating platform, which amounts to an ultimatum. It says that Kosovo’s independence should be fully recognised without any preconditions and that Serbs neither have, nor are entitled to any right to influence the solution of this problem. Washington has swallowed this. I even think that more likely than not Washington itself is behind Pristina’s unacceptable step. Europe is still keeping silent, but I think that it is unlikely to make Pristina-based leaders change their absolutely arrogant position.

The string of gambles that started in 1999 continues to this day. We can see the strengthening of the line for replacing universal international law by the rules invented in the interests of the United States and its allies alone. This line must be opposed.

Articles by this author

Articles by this author

Stay In Touch

Follow us on social networks

Subscribe to weekly newsletter